A few weeks ago I participated in a trip hosted by City of Refuge Ministries, a not-for-profit NGO that works to eradicate child trafficking around Lake Volta. The organization was founded around five years ago by a Nigerian man named John and his American wife Stacy. Every semester a few NYU students volunteer at City of Refuge, and with each new class a group of students attend the Reality Tour.

|

| Lake Volta in Ghana |

|

| Lake Volta |

Lake Volta is the biggest body of water in Ghana and the largest man-made reservoir by surface area in the world. It is widely known for having child slaves, as the practice is ingrained in the culture and economy of the area. Child trafficking is illegal in Ghana but the laws are actively unenforced; the government purposely hands off responsibility to NGOs, preferring free and devoted labor to developing its own commitment. Around Lake Volta, the majority of residents’ livelihoods depend on fishing. Child slaves provide many useful functions for fishermen including paddling boats, untangling nets, and scooping water out of a broken boat.

|

| A child slave; behind him, the slave master |

We left City of Refuge at 1 AM on a Friday, packed onto a bus with about 15 people and tons of supplies. It was a seven-hour drive to the lake, and we arrived in time to catch the morning ferry. From the other side of the lake we drove another hour or so to our host village.

City of Refuge works in seven villages around Lake Volta, and is always looking to expand their sphere of influence. The first activity of the weekend was to travel to a new village and make first contact with the people of the community. John asked what the chief knew about the presence of child trafficking in the village. The chief claimed to be firmly against the practice and said that all of his children attended school (trafficked children are put to work during the school day). We walked to see the village’s school, a small and simple concrete building with a few desks and chalkboards. Afterwards we stopped to talk to a group of children, upon seeing malnourishment and advanced muscle development indicative of child slavery.

| ||

Shores of a village on Lake Volta

|

|

| School |

|

| The trafficked boy |

You may think, how would that work? Why would someone who has already sold or bought a child slave suddenly change his mind? These are questions that I asked when I first heard what John and Stacy do to rescue the children. But believe it or not, this method is effective. The approach that City of Refuge takes to eradicate child trafficking is exceptional. Unlike the other NGOs that work against child trafficking around Lake Volta, City of Refuge uses no forms of coercion or bribery to rescue children. They appeal to conscience, common sense, and human decency.

John describes what he says to a slave master, What did this child do to deserve this as his life? Is he not worth schooling, a childhood? The master scoffs, says that this is how he grew up and he turned out just fine. It is part of life here. John wonders how it felt to be sold as a child slave, to be prematurely worked to the bone? To see your life as a transaction, your body as a commodity? John watches his eyes fall, and sometimes immediately, sometimes eventually, the master gives up his slaves. And he doesn’t buy any again.

|

| More slaves of fishermen |

That night as we waited for the wind to calm and our boat to bring us to our host’s house, a man from the village ran to the shore where John and Stacy stood, tears streaming down his cheeks. He confessed to keeping two slaves, and begged the couple to save them. As Stacy hugged him and John spoke about the logistics of rescuing the children, the man breathed freely. A visible weight was lifted from his chest, and his grimace hoped for redemption.

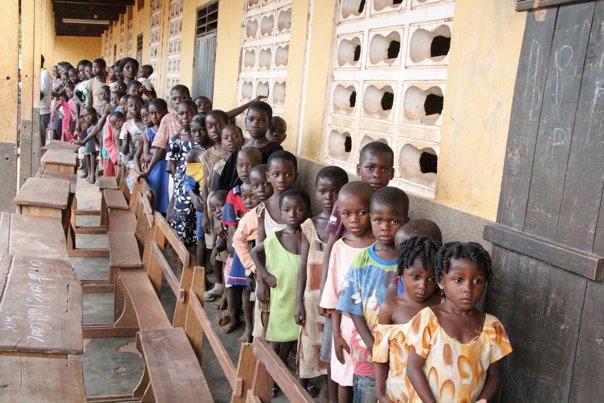

The next day, our group conducted a feed of the children. In the morning our cook made heaping amounts of rice, plantains, tomato sauce, and hard-boiled eggs, and we put together 200 to-go boxes of food. Next we prepared 200 doses of de-worming medication. We would distribute these at the school of another nearby village, whose residents had been told that we were coming. As our bus full of Obrunis came into town, children began to flock to us and line up at the steps of the school.

|

| Preparing food for the children |

|

| Food waiting to be distributed |

|

| In line to be registered |

The mission for the day was to feed, de-worm, and register 200 village children with City of Refuge. As each child stepped across the school’s porch, a volunteer recorded his picture and personal information. Based on a child’s appearance (orange-colored hair indicative of malnourishment, advanced muscle development), familial status (living apart from parents), and personal knowledge (trafficked children often do not know when they were born), we were able to see that many of the children had been trafficked. John and Stacy made some inquiries that day, but the main focus was to register the children.

With the pictures and information, City of Refuge will make identification cards for each of the 200 children. The cards will be distributed in the village, and when John and Stacy return in three months they will serve only children with an identification card. One reason for this is that the de-worming medication lasts for three months, so the same children must get it each time or none of them will be effectively protected. Secondly, this will provide valuable information for City of Refuge to track the children in the village: if they return and a large portion of the registered children is missing from the village, then it is likely that trafficking is a major concern in the community.

|

| Fishermen with child slaves, fleeing from City of Refuge's boat |

City of Refuge is a pioneer in the fight against child trafficking. While most other NGOs and the government shy away from the root causes of the issue, City of Refuge seeks them out. Another investment that the organization is developing is a sachet water manufacturing plant, where mothers from each of City of Refuge’s partner villages will be employed. This will provide women with income and stability at home, negating the need to sell their children as slaves.

|

| Construction of the school is underway |

By impacting the mentality of the community of Lake Volta and empowering its residents, City of Refuge is developing a truly effective and holistic solution to child trafficking. As an aspiring social changemaker, I am refreshed by this approach and inspired to see an organization staying true to the mission of grassroots social change. City of Refuge's actions produce lasting effectiveness that will contribute to the eradication of child trafficking.

All the photos in this entry were taken by Kelsey Vala, awesome photographer and badass chef.

No comments:

Post a Comment